How I navigate the contradictions of doing social class work within capitalism—and what I’m actually doing about it

Head to YouTube for a video version: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FAD6BoK6AFkI’ve been getting comments lately accusing me of not understanding capitalism, or worse, of perpetuating the same harms I’m trying to address in my work on unwritten rules and workplace equity.

So let’s talk about it. Yes, I am a solopreneur, meaning I run a small business. You might see that as selling out, or you might see it as pragmatic survival within the systems we have. Either way, we need to have this conversation.

Let’s Name What We’re Talking About

When people critique capitalism, they’re not being dramatic. There are legitimate, serious problems with how capitalism functions:

Capitalism has never existed without exploited labor. From its origins in chattel slavery and colonialism to today’s prison labor, sweatshops, and gig economy exploitation, capitalism has consistently relied on extracting maximum value from the most vulnerable people while paying them as little as possible—or nothing at all.

It ties all value to labor, but doesn’t value all labor equally. Care work, domestic work, emotional labor—predominantly done by women and especially women of color—is either unpaid or grossly undervalued. Meanwhile, the people who own capital extract wealth without doing the labor.

It requires constant growth on a finite planet. Capitalism demands endless expansion, which is ecologically unsustainable and drives environmental destruction that disproportionately harms marginalized communities.

It concentrates wealth and power. A tiny percentage of people control the vast majority of resources while millions struggle to meet basic needs. This isn’t a bug—it’s a feature. The system is designed to accumulate capital upward.

It commodifies everything. Healthcare, education, housing, water—basic human needs become profit centers. When people can’t afford these necessities, capitalism says “that’s the market working as intended.”

It pits workers against each other. Competition for jobs, for resources, for survival keeps working people fighting each other instead of challenging the people who profit from our desperation.

I’m not going to pretend these aren’t real problems. They are. And they’re not just theoretical—they’re killing people. Literally. People die because they can’t afford insulin. People die in heat waves because they can’t afford air conditioning. People die because profit was prioritized over safety.

So when people say “how can you run a business and claim to care about justice,” I get it. The question is valid.

Why I Don’t Call Myself an “Ist”

I don’t take “capitalist” or “socialist” as core identities. Honestly, I don’t think most people even know what they mean when they use these labels. They shut down. They throw words around without understanding the systems they’re describing.

I know this because I used to be one of them.

Here’s what changed: I’ve traveled globally—a lot. I’ve lived in and visited countries operating under communism, capitalism, and all the spaces in between. I’ve talked with people who’ve experienced these systems firsthand. I’m not operating off book knowledge alone. I’m operating from having seen how these systems actually function in practice.

And you know what I’ve learned? I have yet to find utopia.

Every system has trade-offs. Every system has people who suffer and people who benefit. Every system has corruption and exploitation alongside genuine attempts at fairness and care. That being said, as an American commenting on the American economic system…I will say the system benefits VERY few. It is clearly not working for most of us. (And side note, there’s also the folks that even if you don’t bring up the term “capitalism,” will leave a 3-paragraph rant in YouTube comments talking about how communism sucks, as if there are only two, polar opposite systems in the world *eyeroll.* We don’t even have time to get into THAT in this post.)

But here’s something funny that happens when you talk to people about major issues. Most of us are loud, proud, and confident when we’re asked what we believe and why. However, when asked “how” we tend to have to temper some of our extremes. It’s not as clear-cut. You stop looking for perfect systems and start asking: What levers can we pull? What’s actually possible? What do people need to survive right now while we work toward something better?

The Shift From “Why” to “How”

A lot of self-proclaimed Marxists are very good at analyzing why things are broken. But when I ask “how do we actually change this,” the answer is often vague gestures toward revolution or that nothing can ever be done at all.

Let’s talk about that for a second. The “wait for revolution” theory is loaded with privilege—either you won’t be affected by system collapse and violence as much as marginalized people will, or you’re expecting other people to do the fighting, organizing, and dying for you while you theorize from safety.

If you’re not already organizing, building mutual aid networks, or creating alternative structures now, what makes you think you’ll be doing that work during a revolution? Revolution isn’t a magic reset button. It’s violence, chaos, and the people who suffer most are always the ones who are already most vulnerable. Meanwhile, as we know from the pandemic, most of us can’t skip a paycheck even to stay safe from a deadly virus. Most of us are trying to survive long enough to have the privilege of organizing at all.

When you shift from “why” to “how,” you get more realistic about what’s actually possible and what levers we can pull today.

The Connection Between Culture and Capitalism

I also hear people frequently ask WHY I talk about culture and not “it’s just capitalism.” Because economic systems exist and persist via culture.

Here’s what I know from my decade of research: workplace culture and capitalism are deeply intertwined. The unwritten rules I study—like why certain people are labeled “unprofessional” for being direct, or why working-class professionals get punished for communication styles that differ from middle-class norms—these aren’t accidents. They’re features of a system designed to maintain hierarchies.

I criticize capitalism regularly in my work. My Boeing video breaks down how culture and capitalism intertwine to create literally deadly disasters. You can search “Dr. Kallschmidt capitalism” and find plenty of critique.

You can’t separate capitalism from the cultural norms that make it seem natural, inevitable, or “just common sense.” And you can’t change capitalism without addressing the culture that maintains it.

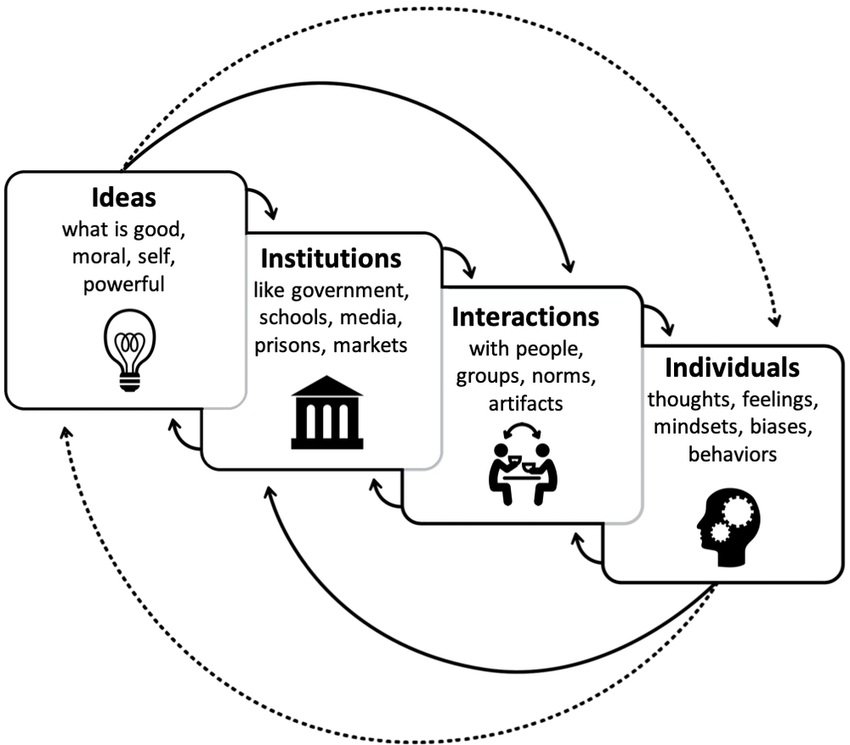

In addition to that case study, let’s get more technical. Let me explain using the Culture Cycle framework from Stanford SPARQ.

This framework shows how change happens (or doesn’t) across four interconnected levels:

Here’s how the Culture Cycle actually operates:

The four levels work symbiotically—they’re dynamically interacting and interdependent. None is more important or theoretically prior to the others. Think of it as a continuous feedback loop.

From top to bottom: The Ideas at the top shape everything below. When the dominant cultural Idea is “shareholder value is the only thing that matters,” that directly influences:

- What Institutions get built and funded (business schools teaching this as gospel, Wall Street structures rewarding quarterly profits)

- How people Interact daily (engineers dismissed for raising safety concerns, workers afraid to challenge bad decisions)

- What Individuals come to believe is possible (“I can’t change anything,” “That’s just how business works”)

In terms of capitalism, these four levels look like:

IDEAS (Cultural Norms – the top level):

- “The only responsibility of business is profit” (Milton Friedman, 1970)

- “Shareholder value is the only thing that matters”

- “Hierarchy is natural and inevitable”

- “Questioning authority is naive”

INSTITUTIONS (Structures):

- MBA programs teaching shareholder primacy as “the only rational approach”

- Wall Street reward structures that incentivize short-term thinking

- Companies hiring executives trained in this model

INTERACTIONS (Day-to-day):

- Engineers warning about safety → labeled “emotional” or “not understanding business”

- Working-class directness → seen as “aggressive”

- Neurodivergent processing → seen as “communication problems”

INDIVIDUALS (Personal level):

- “That’s just how business works”

- “I have to play the game to survive”

- “Maybe I’m just not cut out for this”

From bottom to top: But here’s the crucial part that most people miss—to change those Ideas at the top, you have to push back through all three lower levels. This is why you can’t just theorize about capitalism being bad and expect change.

You have to create pressure by:

- Changing Individuals (helping people recognize systemic issues instead of internalizing failure, building consciousness that “this isn’t natural or inevitable”)

- Changing Interactions (modeling different ways of communicating, rewarding people for speaking up, valuing different perspectives)

- Changing Institutions (creating different business models, changing what gets taught in schools, restructuring how companies operate and who they’re accountable to)

When enough pressure builds at these three levels, the Ideas at the top start to shift. And as those Ideas shift, they create more space for change at the lower levels. It’s a cycle—you can’t change one level without addressing the others, and changes at any level ripple through the entire system.

This is also why cultures are always dynamic, never static. All four levels continually influence each other. A change at any one level can produce changes in other levels over time.

Why This Matters for Understanding Capitalism:

When people say “it’s just capitalism,” they’re typically only looking at the Institutions level—the economic structures, the policies, the laws. But capitalism persists because it’s embedded in all four levels:

- Ideas: “Profit is the only rational goal,” “Competition is natural,” “Hierarchy is inevitable”

- Institutions: Economic systems, corporate structures, business schools, Wall Street

- Interactions: How bosses treat workers, what communication styles are rewarded, who gets promoted

- Individuals: What we internalize as “common sense,” what we believe is possible

You can’t dismantle capitalist structures without also addressing the cultural Ideas that make them seem natural, the daily Interactions that normalize them, and the Individual beliefs that prevent people from imagining alternatives.

The Culture Cycle shows us that economic systems and culture are inseparable. You can’t change one without changing the other. And that means we need people working at all four levels simultaneously.

“No Ethical Consumption Under Capitalism”—The Give Up Tactic

If there’s no ethical business under capitalism, then there’s also no ethical consumption under capitalism…which is another quote that shows up in my comments a lot. People love to throw around “there’s no ethical consumption under capitalism” as if it’s a conversation-ender, especially when someone talks about not supporting a certain business because they don’t agree with its ethics. I see this quote used in two ways:

1. As nihilism: “Everything’s tainted, so why bother trying? Nothing I do matters anyway.”

2. As absolution: “I can’t avoid participating in harm, so I might as well not think too hard about it. Amazon Prime it is!”

Both of these are, frankly, give-up tactics that keep you stuck.

Yes, we all participate in harmful systems. You probably use a smartphone made with exploited labor. You probably buy food from companies with terrible practices. You probably have a bank account at an institution that does harm. Me too.

But here’s the thing: “No ethical consumption under capitalism” is an observation about systemic constraints, not permission to stop trying or an excuse to treat all choices as equivalent.

The full context of that idea (often attributed to anarchist and socialist thought, though no single source) is that individual consumer choices can’t fix systemic problems. You can’t buy your way to justice. The system itself needs to change.

But that doesn’t mean how you participate doesn’t matter at all. It means:

- Individual choices alone won’t fix systems (we need collective action)

- But collective action is made up of individual choices (what you do matters)

- Not all participation is equivalent (there are more and less harmful ways to operate)

- We should focus on changing systems (not just feeling guilty about consumption)

So when someone uses “no ethical consumption” to shut down conversation about how you’re operating, ask: Are they arguing for better systemic analysis, or are they arguing for giving up?

Every Economic System Has Businesses

Here’s something that often gets lost in these conversations: Every economic system has businesses. The question is how they’re organized.

The distinction between capitalism and socialism isn’t whether businesses exist—it’s about:

- Ownership: Who owns the means of production? Private individuals/shareholders, workers collectively, the state, or some combination?

- Accountability: Who are businesses accountable to? Just shareholders, or also workers, communities, and society?

- Power: Who makes decisions? Owners/executives alone, or workers democratically?

- Distribution: Where does profit go? To owners/investors, or reinvested and distributed among workers?

The question isn’t “business or no business”—it’s how businesses are structured and who they serve.

The “Master’s Tools” Question

There’s a famous Audre Lorde quote: “The master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house.”

Some people interpret this to mean you can’t change systems from within—that any use of capitalism’s tools (money, business structures, market dynamics) automatically reinforces capitalism.

But that’s not what Lorde was arguing.

Lorde gave this speech in 1979 at a feminist conference commemorating Simone de Beauvoir’s The Second Sex—a conference that had only one panel with Black feminist or lesbian perspectives. She was critiquing how the conference used the tools of exclusion and tokenism while claiming to fight oppression.

Her actual question was: “What does it mean when tools of a racist patriarchy are used to examine the fruits of that same patriarchy?”

Her answer: “It means that only the most narrow perimeters of change are possible and allowable.”

Lorde wasn’t saying don’t use money or don’t work within institutions. She was critiquing a specific problem: when marginalized people are tokenized—brought in as the sole representative of their position, forced to use their intellectual and emotional labor to address oppression instead of their other expertise. As if the marginalized are equipped to talk about only their marginalization.

As one writer reflecting on Lorde’s work put it: “If the master’s tool is a knife, if that knife is pointed at us, we should try to avoid it, or seize the knife to free oneself, or if necessary, strike back at the oppressor.”

The tool itself isn’t the problem. Whether you replicate the logic of oppression—that’s what matters.

Lorde’s actual critique was about:

- Excluding marginalized voices while claiming to liberate them

- Treating people as tokens rather than full participants

- Using tools of hierarchy and exclusion while claiming to fight hierarchy and exclusion

- Assuming homogeneity and ignoring differences

Her solution? Interdependency across difference. As she wrote: “Without community there is no liberation, only the most vulnerable and temporary armistice between an individual and her oppression.”

Lorde valued “the differences between us as strengths rather than weaknesses,” arguing that “only within that interdependency of different strengths, acknowledged and equal, can generate the power to seek new ways of being in the world.”

This actually supports the need for people working both inside and outside systems. Different positions, different approaches, different strengths—all working together rather than demanding everyone take the same path.

Here’s the question worth asking: What counts as replicating “the master’s tools” in the way Lorde meant?

Is it:

- Using money? Or using it to extract maximum profit while treating workers as disposable?

- Running a business? Or running it with the same hierarchies that exclude marginalized voices?

- Working within institutions? Or tokenizing marginalized people within those institutions?

- Building power? Or building power that only serves people who already have it?

Different people will answer these differently. But Lorde’s actual argument suggests: We can use tools differently than oppressors do. We can seize the knife. We can build interdependent power across our differences.

I Get Why This Is Hard to Grasp

I understand why so many people struggle with the idea that business could be anything other than exploitative. For most people, work has been toxic their entire lives.

When your entire experience has been:

- Bosses who treat you as disposable

- Companies that prioritize profit over safety

- Expectations that you sacrifice everything for a job that doesn’t care about you

- Being told “this is just how it is”

…of course you’re going to struggle with the concept that work could operate differently.

This is the power of the Culture Cycle. When Ideas shape Institutions, Interactions, and Individuals for long enough, those patterns start to feel inevitable. Natural. Just the way things are.

But they’re not.

So how do we change them?

The Inside/Outside Question

Here’s a fundamental question: Do we need people working inside systems, outside systems, or both?

The case for outside-only:

- Systems are designed to co-opt and neutralize dissent

- Working inside means playing by their rules

- Real change comes from external pressure and building alternatives

The case for inside-and-outside:

- External pressure needs internal allies to implement change

- Someone has to be in positions to make policy when movements create openings

- History shows most successful movements had insider-outsider coalitions

Civil Rights Act needed external movement pressure AND insiders to navigate legislative process. Labor rights needed strikes AND people inside government to pass laws. Marriage equality needed activism AND sympathetic judges and legislators.

Which does history actually support? Both.

What I’m Actually Trying to Do

Here’s what I’m interested in: getting people into leadership who give a shit and have strong ethics.

I don’t subscribe to the notion that money inherently corrupts. That’s patriarchal capitalist brainwashing (more content for another post). We’ve created constructs of leadership, of “manliness,” of success that normalize corruption—and then we act surprised when corrupt people seek power. People who aspire for power are often corrupt, and we don’t catch their red flags. We even lionize them sometimes. We fall for the traps of narcissists and psychopaths (they’re good traps; abusers are good tricksters). But they’re getting louder… billionaires are loudly telling us empathy is a bad thing…do we think they care about ethics?

The message has been: “Good people don’t want power. Good people don’t care about money. If you seek leadership, you’re probably corrupt.”

This keeps good people out of positions where they could actually make change.

My goal is to get more people from working-class backgrounds and neurodivergent folks into positions of power—people who actually give a shit about others, who understand what it’s like to not have safety nets, who won’t pull the ladder up behind them.

How I’ve Structured My Work

I’ve made specific choices about how I operate. These are my decisions—you get to decide if they align with your values.

I work at multiple levels of the Culture Cycle:

What I aim to do with my work is address the cultural Ideas that make exploitative capitalism seem natural and inevitable—by working at the Institutional, Interactional, and Individual levels to push back.

When I help working-class professionals understand why their directness is labeled “aggressive,” I’m working at the Individual level—helping them see it’s not a personal failing but a culture clash.

When I help organizations change their communication norms and promotion criteria, I’m working at the Institutionallevel—changing the formal and informal rules.

When I model explicit communication and different ways of operating in my own business, I’m working at the Interactional and Institutional level—demonstrating that other approaches are possible.

All of this creates pressure that pushes up to challenge the Ideas—that “professionalism” is neutral, that hierarchy is natural, that certain people just “aren’t a good fit.”

I offer services at different price points because I believe access matters:

- $8.99 ebook with all my research and frameworks—for people just starting out or who can’t afford more

- $15/month Skool community with weekly group coaching and networking—affordable ongoing support

- $597/module 1-on-1 coaching program (total $3,582 for all six)—for people transitioning to leadership positions

That last one is specifically designed for people moving into higher-responsibility roles that typically come with 15-20% salary increases. We’re talking positions in the $80k-$120k range in the U.S. My full program is about 3-4.5% of that range—and typically pays for itself in the salary increase. I can sleep at night knowing that I’m not extorting people.

I haven’t shifted focus away from culture, marginalization, or intersectionality despite DEI becoming politically dangerous (I didn’t suddenly jump on it either in 2020; I was already doing this then).

I don’t gatekeep knowledge—I have literally thousands of videos in free content on my platforms, and I’m hoping to do more articles like this.

I keep overhead low so I can make values-based decisions rather than desperate ones. I sold my car and my house. I don’t currently have children. These are both privileges and choices that I have made to fuel the life I feel best about.

I have turned down brand deals that do not align with my values. This is where I hear a lot of the “there’s no ethical consumption under capitalism, make your paper.” There’s no perfect company, but if your organization has recently been busted for not paying your suppliers (true story), that does not align with my values as an organization that is pro-working class. I will not be using my platform to promote your products. #sorrynotsorry

I critique capitalism boldly and directly. One of my favorite reviews of my book is that someone said it isn’t “toxically optimistic”—and they mean that as a compliment. I don’t sugarcoat the systems I’m critiquing. And that comes at a business risk. It’s not hot to talk about it. The “big guns” with the big bucks get shy, and it’s going to be harder for me to find a white-collar fallback option if my business fails one day. I know these risks. I’m still choosing them.

And you don’t have to agree with my approaches. You can read these all as excuses. You get to decide if this approach makes sense for you.

Who This Approach Is For

If you want change within existing systems, you need to understand the cultural rules that maintain them. Whether you’re trying to:

- Get into positions where you can change policies

- Navigate corporate environments without losing yourself

- Understand why certain people get promoted and others don’t

If you’re trying to survive long enough to build capital and power:

- Building financial stability so you can take risks

- Getting into positions where you have leverage

- Understanding the game well enough to play it strategically

- Having resources to weather instability

If you’re building alternative structures outside the system, you still need to understand these rules because:

- You need to network with people for funding and resources

- You’ll interact with institutions that operate by these rules

- Understanding the system helps you build better alternatives

If you’re organizing for change, you need to survive while doing that work. And you need to understand how power and resources operate.

If you’re a leader or aspiring leader—regardless of your privilege level—and you want to:

- Build ethical businesses that treat people well

- Reduce invisible class barriers in your organization

- Understand how humans and business can thrive together (not just profit at humans’ expense)

- Create workplace cultures where diverse talent actually succeeds

Here’s something interesting: Companies that make the Fortune 100 Best Companies to Work For® List consistently outperform the market by 3.50 times over a 27-year period, according to FTSE Russell. Treating people well isn’t just ethical—it’s often more profitable long-term than the extractive models we’ve normalized.

Does this contradict the “limitless growth” problem with capitalism? Not necessarily. The issue isn’t growth itself—it’s growth at any cost, growth that requires exploitation, growth that extracts from workers and communities to benefit shareholders. But growth that comes from innovation, from people who feel valued contributing their best work, from retention that reduces costly turnover? That’s a different model. It’s still operating within capitalism, yes. But it’s operating differently than the dominant extractive model.

My work isn’t for everyone. But if you’re from a working-class background, neurodivergent, trying to navigate systems that weren’t designed for you, working to get people who care into positions of power, or already in leadership and trying to do it more ethically—understanding the unwritten rules is essential.

Who My Work Isn’t For

My approach won’t resonate if:

You’re already secure and satisfied with how systems work. If current structures serve you well and you’re not looking to understand or change them, this work probably isn’t relevant to your needs.

You believe engagement with existing systems can’t create meaningful change. I work both within and against systems simultaneously. If you think that’s fundamentally impossible, we’re starting from different assumptions about how change happens.

You’re focused primarily on theory without current action. I’m oriented toward what we can do now—the practical “how” alongside the analytical “why.”

You need certainty and clear-cut answers. This work involves navigating contradictions, operating in gray areas, and accepting that there are no perfect choices. If that ambiguity is incompatible with how you approach problems, this probably isn’t a good fit.

You expect people doing justice work to prove their commitment by working for free. I believe expertise deserves compensation, especially for demanding emotional labor. If that conflicts with your values, we’re not aligned.

You’re looking for reassurance that everything will be fine. I’m honest about how harmful these systems are. I don’t offer false hope or suggest that individual effort alone can overcome structural barriers.

You don’t particularly care about people. If your primary concern is maximizing profit regardless of human cost, or if you see employees as interchangeable resources rather than people, my frameworks won’t serve your goals.

You’re seeking validation rather than information. If you already know what you want to do and are just looking for someone to confirm you’re right, that’s not what this work provides.

My work is for people trying to survive, build power, and create change within deeply flawed systems—or for leaders trying to reduce harm while operating within those systems. If that doesn’t describe where you are, we’re probably not a good match, and that’s okay.

The Questions You Face

You don’t have to answer these the same way I do, but these are worth considering:

On survival and wages:

- How do you survive? Do you work? If so, where’s your ethical line?

- Who typically gets asked to work for free? (Hint: women, marginalized folks, people doing “passion work”)

- Can you help others effectively when you’re one emergency away from financial collapse?

On power and corruption:

- If you believe money always corrupts, how do we fund change work?

- How do people with strong values get into positions of power?

- Should everyone doing social justice work remain poor to prove their commitment?

On strategy and action:

- If you believe change only comes from outside systems, who implements change when external pressure creates openings?

- What are you actually doing? Building alternatives? Organizing? Changing institutions? Supporting others? Or primarily critiquing?

- Are you dividing or coalition-building? Demanding purity or working with people doing imperfect work toward shared goals?

On your own participation:

- Are you using “no ethical consumption” as analysis or as a give-up tactic?

- Who are you expecting to work for free? And who typically receives that expectation?

The Bottom Line

Yes, I run a business. I charge for my expertise. I exist within capitalism while working to change the cultural norms that make capitalism’s worst impacts possible.

You might call that hypocrisy. You might call it pragmatism. You might call it the only realistic option. You might call it not enough.

That’s for you to decide.

But whatever you decide, ask yourself: What am I doing? What do I believe actually creates change? And am I doing that?